Last weekend was ye olde county fair here in Vermont and, of course, we were on the scene to cuddle cows (if you’re Kidwoods) and look askance at cows (if you’re Littlewoods). The county fair also provides a panorama of consumerism. So much to buy, so little time! Annoying, but a fantastic opportunity to practice money management with our children, currently clocking in at ages 5 and 7. Lucky for us, the county fair isn’t the only venue where we’ve been able to broach the thrilling topic of money with our kids lately.

Annoying Instances of Kid-Directed Consumerism We’ve Come Across Recently:

- Museum gift shops: WHY DO THESE EXIST???

- The Scholastic Book Fair: again, WHY?!?

- The County Fair: I’m less outraged at this one, but still mildly annoyed

Our Solution? Bust Out The Family Money Philosophy

In each of these kid-directed-marketing experiences, we fall back on our “family money philosophy,” which sounds a lot more formal and impressive than it is.

It’s actually quite straightforward and brief:

Mom and dad pay for everything you need, including: clothing, shelter, toys, books, games, healthcare, and admission to places like museums and county fairs. We even provide food!

You, child, are then welcome to spend your own money on discretionary items, including, but not limited to:

1. Special snacks/foods/treats outside of what said parent has provided.

A great example here is dessert at a restaurant. Mom and dad pay for the meal but you need to pay for your own dessert if you want one.

2. Trinkets and toys at such places as the county fair and museum gift shop.

Mom and dad pay for admission to the museum and fair, but if you want a souvenir, you have to buy it with your own money.

3. Books from the Scholastic Book Fair.

Mom and dad provide you with a house FULL of books from the library and used book sales. If you want to order something from the book fair, you have to use your own money.

These are the three main consumer options for our girls since we don’t really shop anywhere except the grocery store. But these three provide plenty of avenues for money lessons.

How Does A Kid Pay for These Extras?

We offer our kids the opportunity to do chores on a regular basis with compensation at fair market value. Parents are open to negotiation on a chore price/chore bundle if child feels the proffered amount is insufficient. For example: Kidwoods recently cut a deal with me that if she organized all of the kitchen cabinets and drawers in one day, I would pay her a lump sum of $10. Deal, kid.

Here’s our current list of chore options (which rotate seasonally and with child ability levels):

- Sorting all of the clean laundry into baskets for each family member

- Folding all of the clean towels, rags, etc

- Putting away mom and dad’s laundry (Kidwoods is very good at this and I’m willing to overlook the occasionally mis-filed shirt for the convenience. We did lose a person’s ski sock for several weeks before discovering it was in the cleaning rag box, so this isn’t a perfect system, but it’s good enough. )

- Collecting all of the trash in the house

- Sorting the recycling

- Organizing drawers, cabinets, the pantry, the tupperware, etc (Kidwoods is a natural organizer and excels at this, although the downside is that she then scolds family members who don’t keep it organized. I’ve pointed out to her that this is actually job security)

- Cleaning that I don’t normally bother to do (washing the exterior of kitchen cabinets, washing windows, etc)

- Dishes: washing, putting away, loading of dishwasher, etc

- Miscellaneous chores that crop up

Chores are only paid if the job is done to completion and with minimal adult assistance. For example: you cannot empty the house trash cans but spill 40% of the contents on the stairs and declare mission accomplished. You have to return to the scene of the incident and pick up each individual trashlette you dropped. Just for example.

Our girls go through phases with chores–some Saturdays end up being a chore sprint and the girls clean out my wallet. Other days, no one wants to do any chores for any price at any time whatsoever. This is fine, but the girls are aware that not doing chores = no spending money for them.

Daily Unpaid Work

Our kids also have daily unpaid chores, which are just part of life in a family. These include things like: putting away your own laundry (I only pay them if they put away MY laundry), collecting eggs from the chickens, taking out the compost buckets, cleaning their rooms, making their beds, cleaning up their toys and ephemera, clearing the table, etc. The differentiation is between chores they do to help themselves (such as putting away their own laundry) and chores that help the family (such as organizing the kitchen cabinets). They get paid for the latter but not the former. I always wonder if I’m using latter and former correctly… Here’s hoping I did.

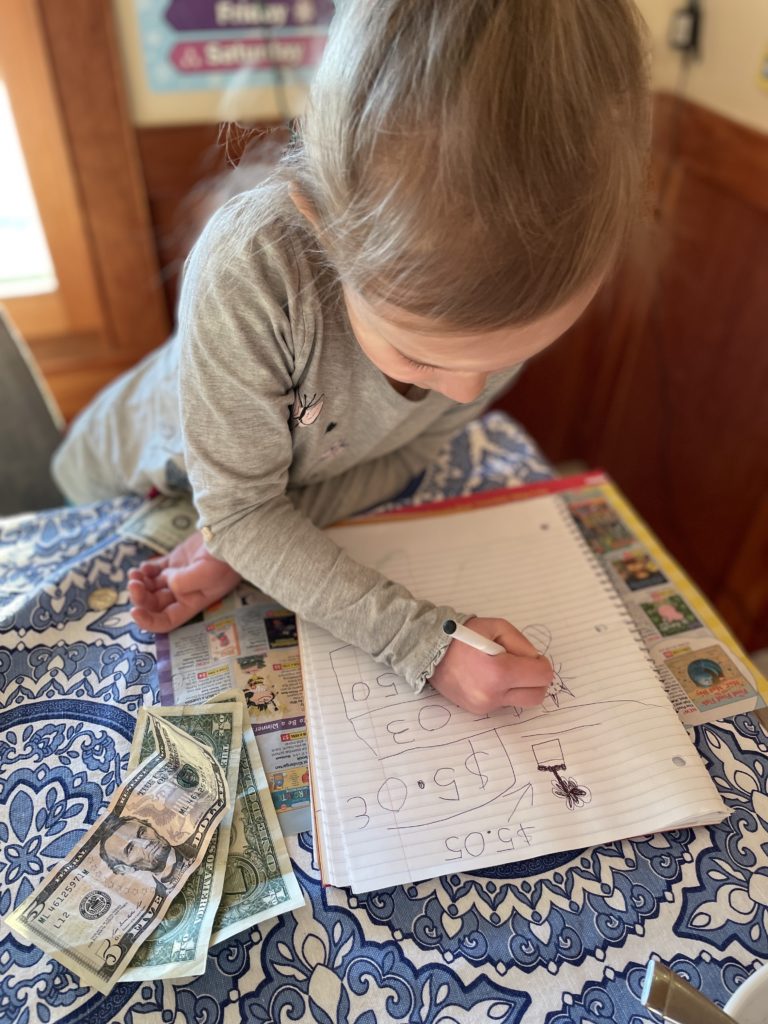

Money Education: Start Super Simple & Super Basic

I view our kids’ financial education as a scaffold–I’m not teaching them about investing for retirement yet because that’s too abstract for a 5 and a 7 year old. Instead, I am teaching them how to count different denominations of money, how to read prices on items, how to comparison shop and how to work for money. My husband and I go out of our way to explain the rudimentary concept of how money works in our society. We often reiterate the following:

Mama works and is paid money for her work. She then uses that money to buy the things that we need and want for our family, such as groceries, clothes and toys.

This is so simple as to seem ridiculous, but I tell you, it’s revelatory for a kindergartener. Kids don’t go around thinking about the fact that adults are paid to do their jobs. Nor do they consider that a car full of groceries represents a certain number of hours worked. By breaking down this equation for them, we’re working to demystify and simplify this weird adult world of money. These super basic explanations also remove judgement, bias, stress and anxiety around money. We’re just laying out the facts so that our kids understand how the world operates.

A lot of parents fear that talking about money is inappropriate for kids or that it’ll cause kids to be anxious about the family’s wellbeing, but it’s all in how and what you share. There’s no need for my husband and I to bring the girls into our investing strategies at this stage just as there’s no need to put the burden of building a household budget on them (yet).

I know this is sinking in on some level because Kidwoods recently presented me with a “book” she’d written about my job. I sometimes let her read a book in my office while I work so that she has some sense of what I do when I’m in here typing away at my keyboard. The salient parts of her book read as follows:

“…her job is to help other people with their money. She does a lot of meetings. The meetings are very boring. But they are really important. They drink coffee and tea. They are serious but kind.”

She nailed it. Although I would disagree with the assessment that my meetings are “boring”…

In general, I am trying to demystify money for the kids and help them view it as what it is: a tool. Money is not status, self-worth, emotional wellness, happiness or contentment. Money can certainly be used to buy those things–to an extent–but it’s just a tool like any other. Exercise, good food, sleep, water, safety–these are also tools that can help you achieve those desired ends.

You Are Responsible For Your Own Money

Another pillar of these early money lessons is the fact that our kids are responsible for keeping track of their own money. The girls each have their own wallet and purse, in which they (are supposed to) store the proceeds from their chores. Kidwoods (at 7) is better at this than Littlewoods, but both are getting the hang of the idea that money should not be stuffed into the bottom of your stuffy basket. Or in the memorable instance of my friend’s son: crumpled up and thrown into the trash.

If You Want to Spend Your Money, You Have To Remember to Bring Your Money

Mom and dad do not keep your money for you, nor do they preemptively bring your money places for you (unless you specifically ask us to do so). This is something we’re still working on and there’ve been quite a few tears over forgotten wallets. I want the girls to take full ownership over their money and remember that if we’re going somewhere like the county fair, they might want to bring their money.

You also can’t lose your wallet. We had a near crisis-level incident at the science museum gift shop earlier this summer when Kidwoods misplaced her wallet. She’d gotten herself this far: earned the money, put it in her wallet, remembered to bring her wallet with her and then, right at the moment of purchase, misplaced it. I had her go up to the cashier to ask if anyone had turned in a sparkly wallet with hearts on it and, lo and behold, they had. Tears of relief flooded her tiny face and she gulped them back in order to purchase the butterfly ring she’d spent roughly 3 hours selecting. This near total loss freaked her out but again, provided us with a perfect real-life example of the importance of keeping track of your stuff. She asked how you get your money back if you lose it and I had to explain to her that, often, you don’t.

Why I Let Kidwoods Go Into Debt: You Can Only Spend What You Have

This is perhaps the toughest lesson of all and a lesson that a lot of adults still struggle to internalize. At last year’s county fair, there were inflatable unicorns for sale. Kidwoods fell deeply in love with a turquoise one and was adamant that she wanted to spend her money on this plastic horse with a horn. As it turned out, the unicorn was $13 and she only had $9. I told her I was willing to pay the extra $4, but that she’d have to work off her debt. She agreed and clutched her unicorn with glee. Once home, the reality of “work off your debt” began to sink in. I explained that, since she was in debt, chores-for-payment were not optional until she’d re-paid the $4 I’d lent her. Chores were now required. After a solid hour of work, she remarked:

“It is not fun to do chores to earn money for something I’ve already bought. This is a lot of work and I’m not getting anything!”

This was, again, a very basic lesson: don’t spend more money than you have. But it’s something kids have to experience for themselves. I allowed Kidwoods to go into debt because I wanted her to know the feeling she articulated above–that it stinks to work to pay for something you’ve already bought. Me explaining debt to her in the abstract would do nothing to help cement this visceral understanding for her.

This happened over a year ago and neither girl has gone into debt since. I’m not saying they won’t ever go into debt in the future and I’m certain this lesson will need to be repeated over the years. And that’s fine because I think allowing kids to go into debt exemplifies the crucial elements of:

- Start with very basic money concepts

- Let kids experience all steps of the process–positive and negative–themselves

- Enfranchise kids to earn and spend their own money on whatever they want:

- They will not have as much buy-in if it’s your money

- Parents seem to have an endless font of money and unless kids have to use their own money, it’s a meaningless exercise for them

Plan Your Spending

Based on this unicorn-induced debt experience, Kidwoods is now much more aware of how much money she has and how much she’s likely to need for any particular spending sojourn. Over the summer, we periodically went to pizza night at a nearby farm where we–the parents–purchased pizza for everyone to eat. The farm also sells desserts, but the parents weren’t going to purchase any. Kidwoods decided she’d start buying her own desserts. She knew the price of the dessert (mercifully it never changed and was always $7) and she knew she’d share it with her sister.

Initially, Kidwoods paid for the dessert herself and shared it with Littlewoods. After a few weeks, however, Kidwoods pointed out that she was earning and spending all of her money on a dessert that was also benefiting Littlewoods. Not having a leg to stand on in this argument since she had indeed been eating half of these desserts, Littlewoods agreed they could split the price. A secondary crisis ensued when Kidwoods noted that $7 can’t be divided evenly. A great opportunity to re-visit counting coin denominations! We also had the girls go up to the counter to order their own desserts, pay for them and bring them back to the table by themselves.

In all of these instances, I’m trying to enfranchise our kids to manage each step of the process on their own:

Earning money, saving money, planning purchases in advance, and then executing the purchase in real life (as independently as possible).

Up Next: A Savings Account!

What we have yet to convey to them in a meaningful way is the concept of long-term savings. My next money lesson plan is to open up a Bank of Parental Units that will pay interest on their savings. So far, the girls spend almost all of the money they earn, which is fine. They needed to first learn these very basic elements of earning, counting money and spending. Now, I think Kidwoods is ready to learn about interest rates and the advantages of saving. I’ll let you know how it goes!